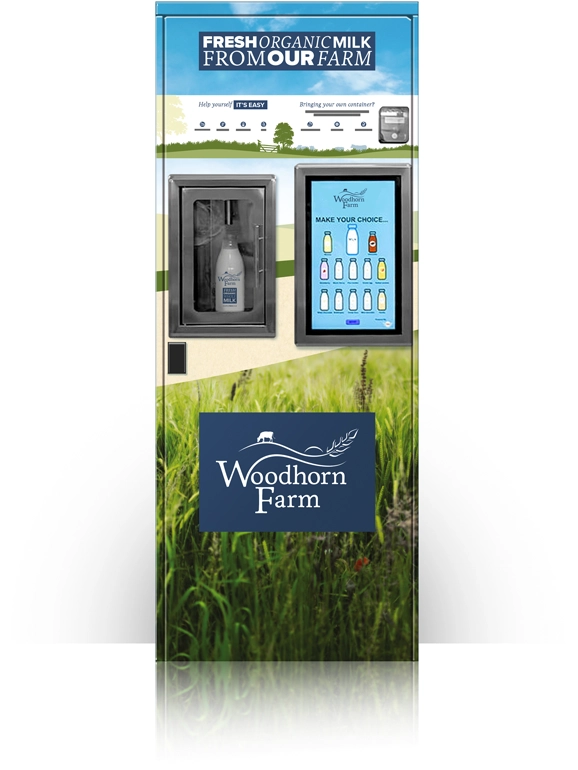

Another year, another drought! Another ‘Down on the Farm’ article, another frustrating delay to our milk vending project!

The latter is down to the continued delay of the supply of our pasteurising equipment. The only manufacture of the particularly specialised kit that we need is in Ireland and they have singularly failed to meet their promised delivery schedule. I sincerely hope by the time I write my next article we will be up and running. In the meantime, please help us choose our first milkshake flavours here.

Weather extremes, a principal feature of climate change, are becoming the norm.

This year we had the driest February on record when just 3.8mm (0.1 inches) of rain fell. Compare this to our February historical average of 60mm (2.4 ins). Conversely, we had the wettest March and April for many years with a combined total of 148mm (6 ins) compared to an average of 52mm (2.1ins) for the same period. June and July are looking exceptionally dry like last year.

We aim to complete all our spring sowing in March, but the ground was so saturated that much of this was delayed until May. This significantly reduces yield potential and some fields or part of fields never dried out enough to sow at all. The high temperatures and lack of rainfall now is restricting grass and clover growth, both for grazing and to make silage for next winter’s feed reserves.

Farmers Weekly has just run an in depth article “Dairy Farming in a Drought” which essentially takes the experiences of dairy farmers in New Zealand and Australia where droughts are the norm. My two ‘take aways’ following a bit more personal research, were how New Zealand dairying (one of largest producing countries in the world and the biggest contributor to its economy) manages drought with huge amounts of irrigation. However, this is becoming environmentally unsustainable as natural groundwater supplies are diminishing causing rivers and lakes to dry up, with over 60% severely polluted due to the intense use of artificial nitrogen and phosphate fertilisers which ‘runs off’ the land into the waterways, where the problem is exacerbated by the lack of water to create a dilution effect.

Australia’s farmers tend not to have the same access to irrigation and so the country has a significant and growing shortage of milk and dairy products forcing it to import much of its needs.

We are, as a nation and like Australia, importing more and more food. However, this is not (yet) because of drought but because of the power of the supermarkets and a lack of government interest in a food strategy generally. Like New Zealand, our water supplies are under pressure though but more as a result of our ever increasing population than from the needs of farming. However, as droughts become more common, the demand for scarce water supplies from both farming and people will increase. However, we continue to be blessed by guaranteed and plentiful winter rainfall. If we, as country and as farmers, invest in adequate infrastructure to collect and store that winter rain, we can meet all of our needs. The cost though of such infrastructure is inevitably enormous at both national and farm level.

After last year’s drought, we made some investment to create the ability to irrigate and we will do more over time. It is an expensive and challenging direction of travel, but one I think will be essential if we are to continue to grow food for our nation. Farming Organically (and so we don’t use the polluting fertilisers and chemicals) and if we are able to store winter rainfall, we will not cause the pollution problems seen in New Zealand

Harvest is not far away now and the harvest machinery and grain stores will be getting their final checks. Calving at Reeds farm starts in mid August. We will be starting the Organic conversion at Madame Green Farm immediately post-harvest and will be sowing a variety of legume (clover and vetch for example) based crops which will start to rebuild the soil’s fertility and organic matter during the statutory conversion period – one can only sow the first organic crop two year’s after the last chemical or artificial fertiliser was applied, which means it will be nearly three years before we will harvest our first Organic crop.

John Pitts

Recent Comments